CP&A on Wind Loads at Port Conference

Casper, Phillips & Associates Inc. (CP&A) has delivered a well-received presentation about wind load calculations for container cranes, at the Port & Terminal Technology Conference, which took place at the InterContinental at Doral, Miami, Florida on April 29-30, 2025.

The paper, titled, ‘Don’t Get Carried Away by Wind Loads’, was given by Richard Phillips, mechanical engineer at CP&A. Phillips addressed a delegation including representatives from operations, maintenance, and engineering teams at port authorities, terminal operators, consultancy firms, dredging contractors, maritime construction businesses, consulting engineering organisations, and suppliers of cargo handling and terminal equipment. The event was hosted by MCI Media Ltd.

CP&A offers a wide variety of services, including procurement, specification, design, manufacturing review, modification, and accident investigation. Phillips centered his session on the length of time that is used to calculate wind speed measurements. He explored the “chaotic behavior” of wind and explained how it is considered by crane designers. He went on to compare and contrast different design codes and the fact that, even within a certain region, cranes and wharves will likely be designed to different criteria.

Phillips said: “Pretty much all significant structures consider wind loads. The issue is that many structures, including quayside container cranes, may be designed to different standards, and there is often inconsistency between the definitions of wind speed. Many designers believe wind load is the most confusing and unpredictable variable they have to consider. Wind is turbulent; it is highly variable in both time and space. At any given moment, the various surfaces of a structure are subject to different pressures.

“Containerization is the key link that enabled globalization and continues to play an important role in the global supply chain. However, inconsistent wind definitions can complicate the procurement process. Different regions have different design practices. Even today, certain regions define environmental hazards, such as wind loads, differently. Cranes and the wharves they operate on are almost always designed to different codes.

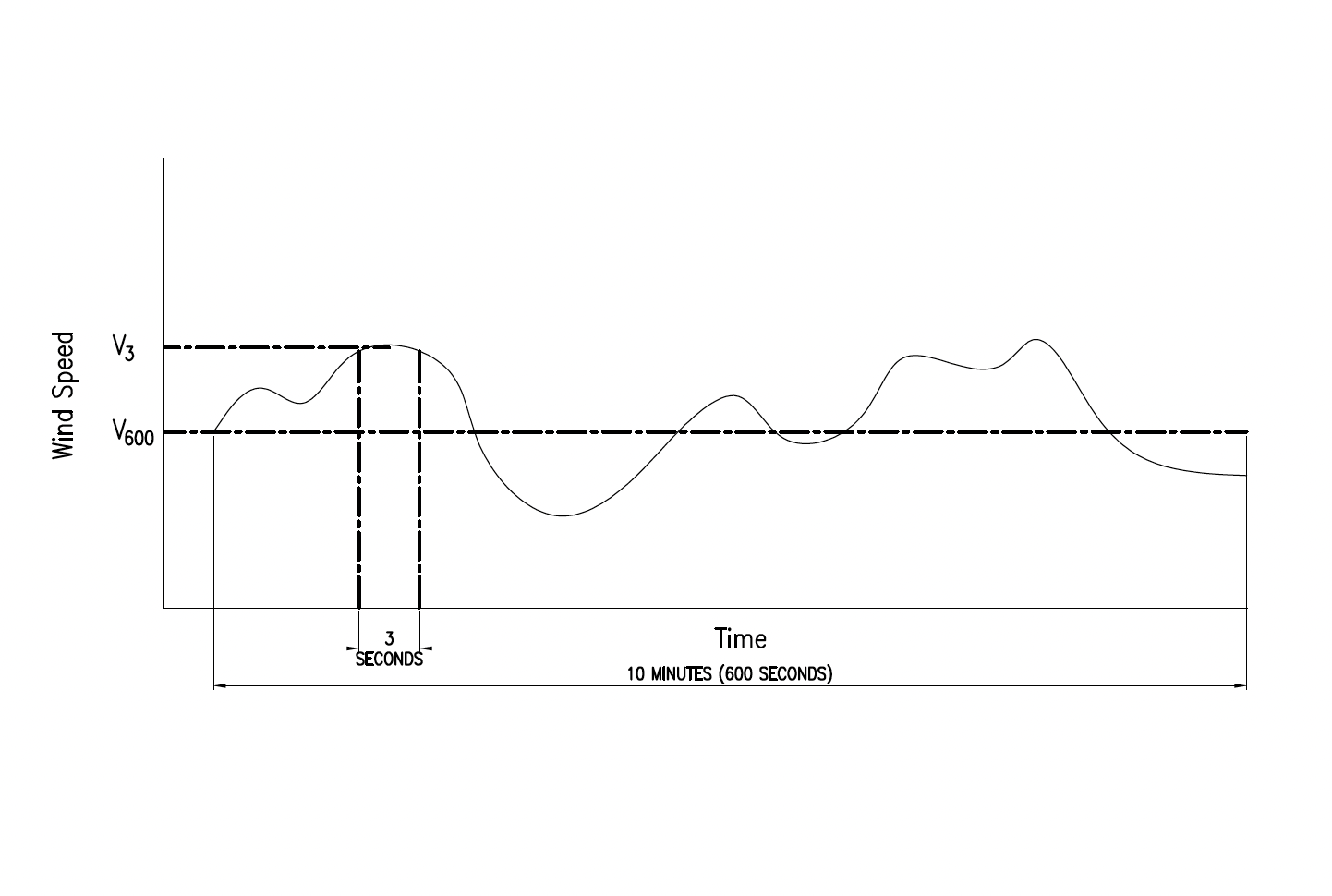

Richard Phillips, mechanical engineer at CP&A, used this graphic to explain to Port & Terminal Technology Conference delegates how wind speed is measured.

“Different averaging times have a big influence on the wind speed,” Phillips continued. “The example [shown at the event] was based on a 10-minute average and a three-second average. For the same 10-minute data set, the 10-minute average will be the average of the full data set. Some measurements will be above and below the average recorded wind speed. You can find a three-second subset of data points that will have a higher wind speed. This is why averaging time is so important. Depending on how long of an interval you average your data, you will get a different wind speed recording, even when using the same data set.”

Storm return period

As delegates learned during the presentation, the storm return period is another important consideration. This is the accepted period of time before a storm of a given size is expected to return (every 50, 700, 2000 years, etc.). For context, Phillips explained that for the venue of the conference, a 50-year storm is 127mph and a 700-year storm is 166mph. A wharf may support several generations of cranes, so it is more likely to see a larger storm since wharves typically have longer design lives than cranes. Typically, the wharf is designed for a longer return period.

An enduring problem with design codes is that it is unlikely there will ever be significant movement toward international harmonization of wind load standards for port infrastructure. Codes tend to be deeply rooted in regional practices, local climate data, historical performance, and even legal frameworks. Phillips is among stakeholders campaigning for continued improvement of communication.

Richard Phillips, mechanical engineer at CP&A, also explained to Port & Terminal Technology Conference delegates how to refine analysis by using a boundary layer wind tunnel (BLWT) test to calculate a more realistic wind load.

He said: “What we’re more likely to see, and what I think is a more realistic goal, is increased awareness and better communication across disciplines and regions. That means crane manufacturers, port engineers, and dock designers need to be proactive in identifying which code assumptions are being used and how they affect the final design. As we discussed, cranes and wharves are designed to different codes; as the old guard passes the torch to the next generation this needs to be emphasized.

“As design codes evolve, they become more and more complex; and different design codes may go about accomplishing the same goal differently. It means communication is key. As we push the limits of our designs, we need to revisit design practices and ensure our assumptions are still valid.”